Did you know that the ACWM has more than 120,000 artifacts in its collection? Did you know that 100,000 of them are documents? The rest are objects, lots of guns, swords, flags, uniforms (whole or in parts), and other bits and pieces of military and homefront life during the Civil War era. A tiny portion of those objects are carvings made by prisoners of war from the detritus of war–materials that any laid-up POW would be likely to find on or around their person, including wood, bone or shell, and metals both precious and not.

These objects tend to be reminders of normalcy or practical need like buttons, or chess pieces, or mementoes of home like sugar bowls, thimbles or soup ladles. Tiny bible charms or crucifixes were common expressions of faith turned into easily concealed talismans to see them through their more trying times. Chains were very common–reputed most often to be made from a single piece of bone or wood, they were also made by forming slender tubes that were sliced into tiny sections. Jewelry was also made, from the intricate earring and brooch set of full-blooming roses made of beef bones, to badges.

One day, while reading the labels for many of these POW carvings, I began to notice a single material repeated frequently: gutta-percha. “What,” I thought, “is ‘gutta-percha’?” I’d never heard of it, but clearly gutta-percha was readily available to the soldier behind bars. So, what on earth was it and where were they getting it? A swift Google search gave me endless scientific papers on its use in dental work today, but has it always been so? Were these Civil War POWs pulling gutta-percha from their teeth to create beautiful inlay patterns in tiny Bible charms?

Well, not quite. Gutta-percha is tree sap that has been used by the people from the regions known today as Malaysia and Indonesia for hundreds of years as a latex or plastic-like material in knife handles and walking sticks.1 Its first medical and industrial uses by Europeans date to the 1700s.

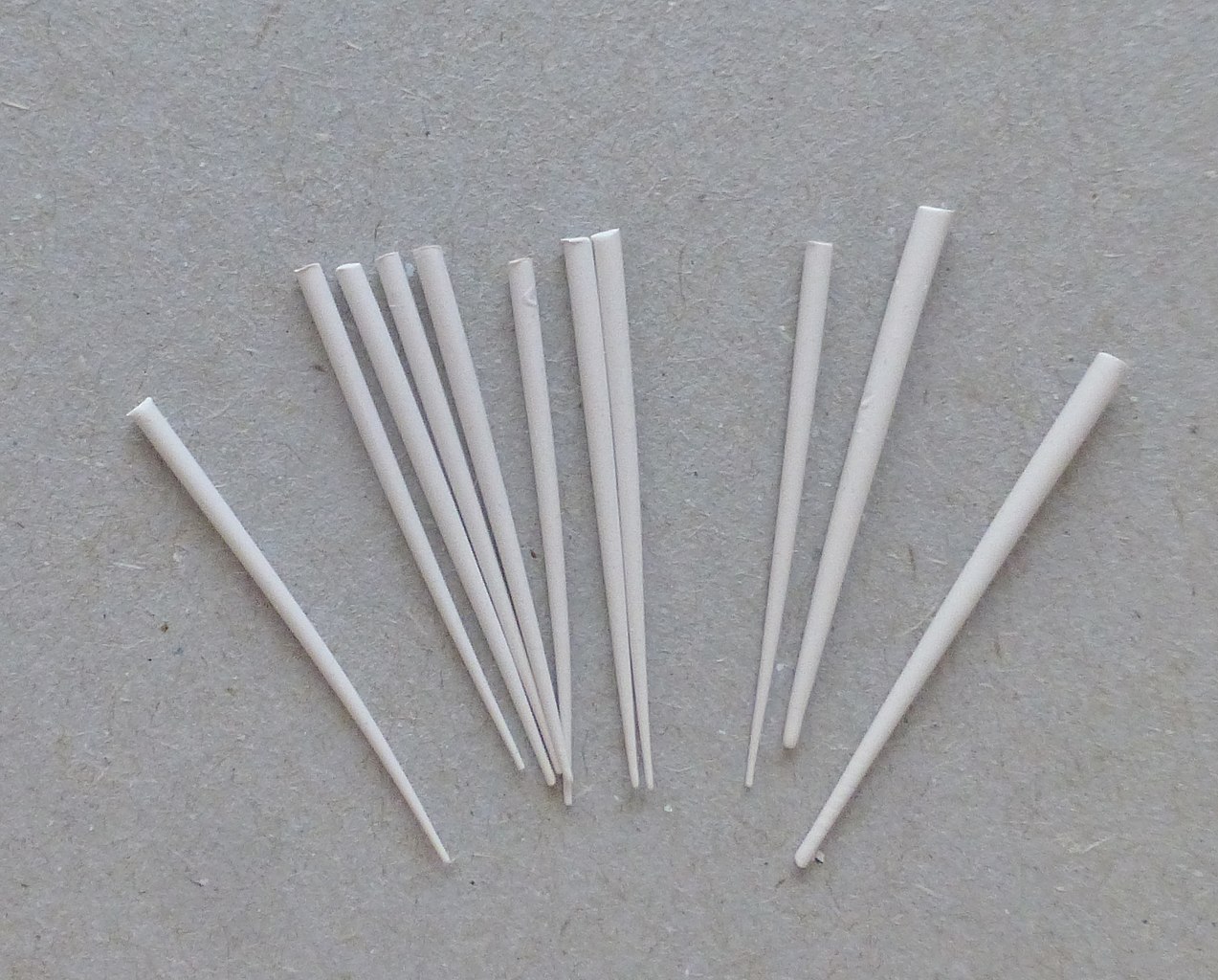

Derived from the sap from the sapodilla tree, the resin-like material was harvested for industrial use as an insulator for underwater telegraph cables, but was also also used for more domestic items: furniture, mourning jewelry, pistol handles, and walking sticks. It was easy to carve and polished up nicely. Considering how common pistols were during wartime and how fashionable walking sticks (canes) were for men of the day, it isn’t hard to imagine these items being worn out, broken or left behind in the chaos, and their gutta-percha parts becoming the raw material of POW works of “art.”

Golf balls were once made of gutta-percha and known as “gutties.” Today (according to the Colgate company), the material is used as a permanent filling in root canals. (What’s in your mouth?). A more scientific source states that for endodontics “gutta-percha has stood the test of time.”

The cane was supposed to be mightier than the quill in this 1856 political cartoon depicting the Brooks-Sumner Affair, in what is probably the most infamous use of a gutta-percha object. Here we see a cane made of said material used in the vicious attack on the anti-slavery US Senator Charles Sumner (Massachusetts Republican) by the pro-slavery US Representative Preston Brooks (South Carolina Democrat) on the floor of the US Congress in 1856. Way to win friends and influence enemies… In the end, the 37-year-old Brooks was censured, resigned, re-elected the next year and then promptly died, while Sumner slowly recovered and served another 18 years in office.