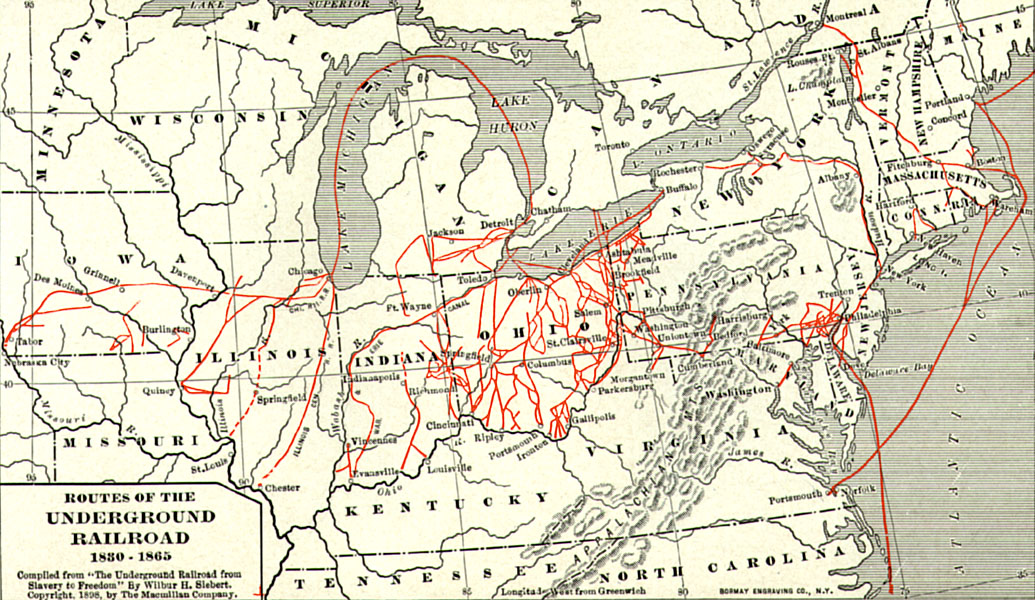

Featured Image: Map of the Underground Railroad. Tubman used the route which ran from Maryland to Wilmington, Delaware, then to Albany, New York.

When you hear the name Harriet Tubman what comes to mind? Most people know her as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and some might know that during the American Civil War she served as a scout and a nurse. To many, she was the Moses of her people, and to John Brown she was “General.”

The fact that so many people (even people who do not have a particular interest in history) know who she is and what she did says something about her impact. Just think about it—she was both an African American and a woman from the nineteenth century, and, yet, she is known by most Americans today.

More children’s books have been written about Harriet Tubman than any other African-American historical figure—including Frederick Douglass. Although much of what we know about Harriet Tubman is based in truth, she is an example of the phenomenon “if the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Her exploits have been magnified almost to the extent that the courage and fighting spirit she possessed to execute them has been taken for granted. She has been portrayed more as a superhero than as a flesh and blood woman with all the feelings and emotions that accompany being mortal.

But Tubman, or Araminta Ross, as she was first called, was very human. She was born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland between 1815 and 1825, and from the early age of five, she was hired out to do a variety of jobs. By the time she was an adult, she could chop and tote as much wood as most men; although she stood only five feet tall.

Harriet (she took her mother’s name after seizing her freedom) felt the full oppression of slavery from the physical brutality (her enslavers beat her, and once struck in the head by a weight that resulted in a lifetime impairment) to the emotional pain of seeing her sisters sold South. She determined she would not be sold and made the decision to escape. For the unknown world of the North, she left behind everything she knew, including her husband, John Tubman.

The recent movie “Harriet” gets these personal details wrong, John Tubman never offered to flee with her. In fact, Harriet begged him to come with her to start a new life, and John Tubman, despite being a free man, refused. On a side note, but one illuminative of Harriet Tubman’s character, she took her marriage vows so seriously that she did not remarry until after her husband’s death in 1867.

Because the dramatic story of Tubman’s escape is so familiar to us, the amount of courage it took to make this move is often overlooked. There was no certainty that she would obtain her freedom and not be recaptured or worse, and a successful life in the North was not guaranteed.

Sarah Bradford, the author of Tubman’s first biography, interviewed her in 1869 and quoted Tubman, describing both the exhilaration and alienation of her arrival in the “promised land.”

“I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home, after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free. I would make a home in the North and bring them there, God helping me.”

Determination that her family should be free is what drove Harriet Tubman to make perhaps as many as nineteen trips back into Maryland. Estimates of the number of enslaved people she rescued vary. Sarah Bradford claimed that Tubman rescued 300 people, but Kate Lawson, a more recent biographer, says her research has confirmed 70, with her indirectly providing instructions to another 70 people. Tubman, herself, only claimed to have rescued 50 to 60 people.

Whether the number was 70 or 300 is moot. Rescuing herself was an act of courage; rescuing others personified courage and self-sacrifice. These two traits dominated Tubman’s life—from her initial escape to her determination to wrest fugitive slave Charles Nalle from the legal authorities in Troy, New York, to her work as a scout for the U.S. Army and participation in the Combahee River Raid, to running a home for aged and infirm people of color.

Tubman’s faith was the hope and anchor of her life. It sustained her in times of need and empowered her to live for others. Her Quaker friend, Thomas Garrett who operated a store in Wilmington, Delaware, that served as a station on the Underground Railroad explained, “She has frequently told me that she talked with God, and he talked with her every day of her life, and she has declared to me that she felt no more fear of being arrested by her former master, or any other person, when in his immediate neighborhood, than she did in the State of New York, or Canada, for she said she never ventured only where God sent her.”

Yet, Harriet Tubman’s faith did not quench her fighting spirit. She knew slavery’s evil all too well. Using violence to combat the most violent of institutions was not a contradiction to her. She wholeheartedly supported John Brown and would have participated in his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had she not been ill at the time. Although historians may dispute the extent of her role in the Combahee River Raid, which resulted in the emancipation of 725 people, the information she and her scouts provided was vital to the raid’s success and may have inspired it. Undoubtedly, her presence on board the boat reassured frightened enslaved people that a rescuer had arrived.

It is not an easy thing to venture all, to take a stand when faced with opposition, or to live a life of service to others. Tubman did all of this and more. She deserves our praise and to be remembered as a hero, but when we forget Harriet Tubman’s humanity, we lessen her achievements.

By Kelly Hancock, ACWM Interpretations and Programs Manager.