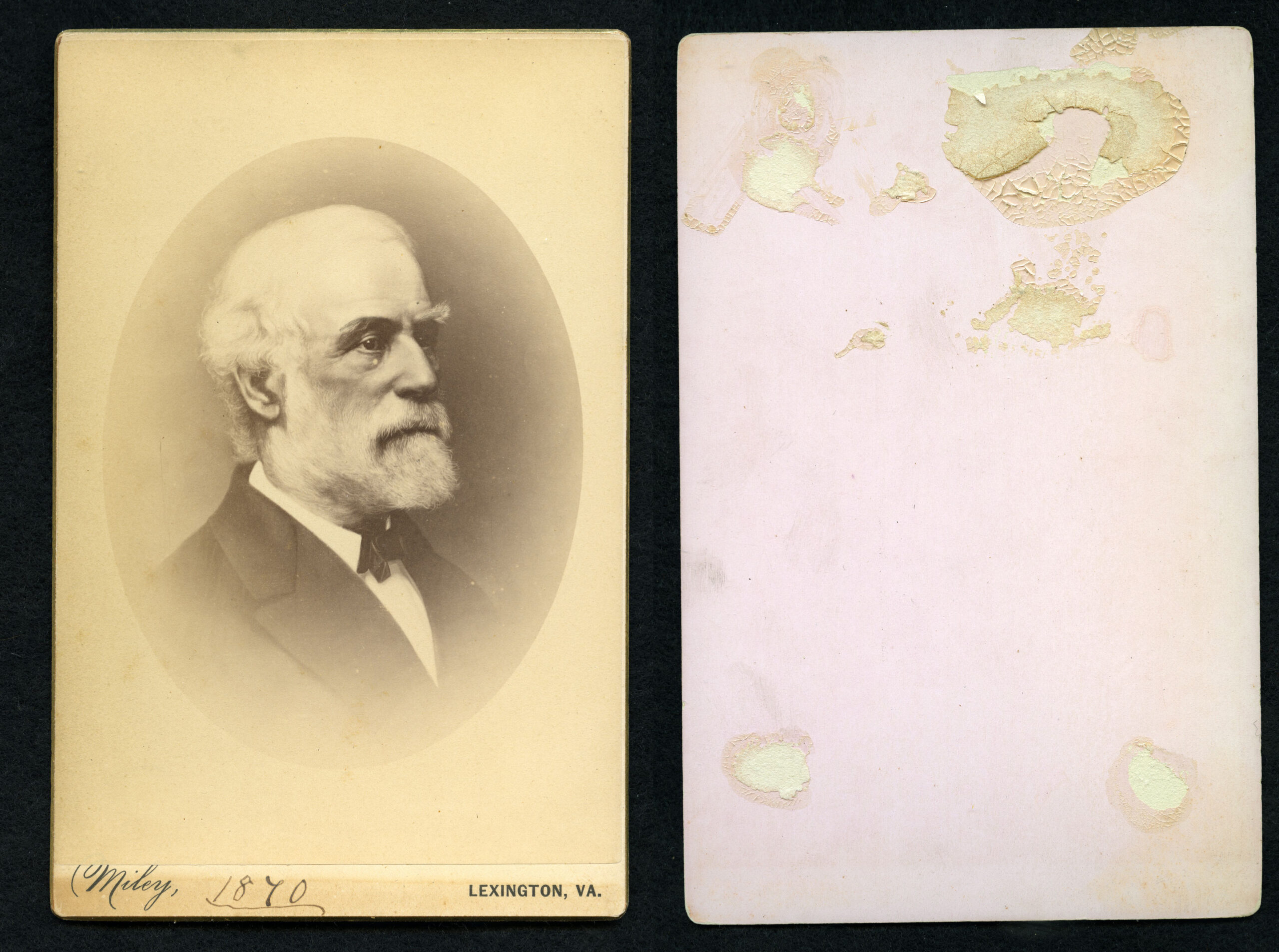

One hundred and fifty years ago today, on October 12, 1870, Robert E. Lee died at his home in Lexington, Virginia, from complications following a stroke suffered two weeks earlier. Torrential rains flooded local roads, preventing all but local mourners from attending his funeral on October 15.

Within days, a group of Lexington citizens met to organize a Lee monument association. Their work resulted in Edward Valentine’s recumbent statue of Lee, unveiled in 1883 over the crypt where Lee’s remains were placed in what would be known as the Lee Chapel at Washington & Lee University.

On October 24, 1870, former Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early broadcast an announcement for a meeting of the surviving officers and men of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to be held in Richmond on November 3. Unable to give “expression to our feelings” at the funeral, Early wrote, “we owe it to our fallen comrades, to ourselves, and to posterity, by some suitable and lasting memorial, to manifest to the world, for all time to come, that we are not unworthy to be led by our immortal CHIEF, and that we are not now ashamed of the principles for which LEE fought and JACKSON died.”

On May 29, 1890, after 20 years of several false starts and many twists and turns, Richmond unveiled a heroic scale equestrian statue of Lee on Monument Avenue. The keynote address celebrated Lee as an apostle of national reunification and an honorable man of character whom the entire nation could admire and emulate. Indeed, by the centennial of Lee’s birth, in January 1907, Lee had achieved the status of national hero – and he maintained that status throughout the 20th century, honored even by the government that he fought against during the Civil War.

Today, 130 years after its unveiling, Richmond’s Lee monument still stands, but only because pending court proceedings have prevented the implementation of the Virginia governor’s order to remove it. The circle in which the statue stands has become the epicenter of an ongoing protest movement that traces its roots back to “the hoarse cry of ‘treason’” that Jubal Early decried in his October 1870 announcement, and to the viewpoint that African-American city council member and newspaper editor John Mitchell, Jr., articulated in 1890 – that the statue “serves to retard the progress in the country and forges heavier chains with which to be bound.”

To learn more about Robert E. Lee, watch this lecture by historian Barton Myers at the Civil War Institute.