Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney created the Monument Avenue Commission in June 2017 to provide context for the Confederate statues that he believes offer a distorted picture of Richmond’s history. Stoney asked the Commission to explain “the monuments that currently exist,” and “to look into and solicit public opinion on changing the face of Monument Avenue by adding new monuments that would reflect a broader, more inclusive story of our city.”

The five Confederate statues unveiled on Monument Avenue between 1890 and 1929 are not, of course, the only statues along that famous road. As Stoney noted – and as this blog has explored – a statue to Richmond-born tennis champion and humanitarian Arthur Ashe was unveiled in 1996 after years of divisive, but ultimately cathartic, debate about the meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond’s identity and civic life.

The Ashe statue drama demonstrated that Monument Avenue would not remain forever an exclusively Confederate memorial, and that Monument Avenue was – and likely never will be – a finished product. Although both of these revelations caused widespread consternation in the 1990s, they were foreshadowed in an extensive public discussion 30 years earlier – a discussion that is remembered only for one sensational reason.

Every few years, the Richmond media rediscovers a lost opportunity for the city to have become home to a statue that would have married the traditional with the surreal. In 1966, the colorful Spanish artist Salvador Dali proposed a statue depicting Confederate hospital administrator Sally Louisa Tompkins.

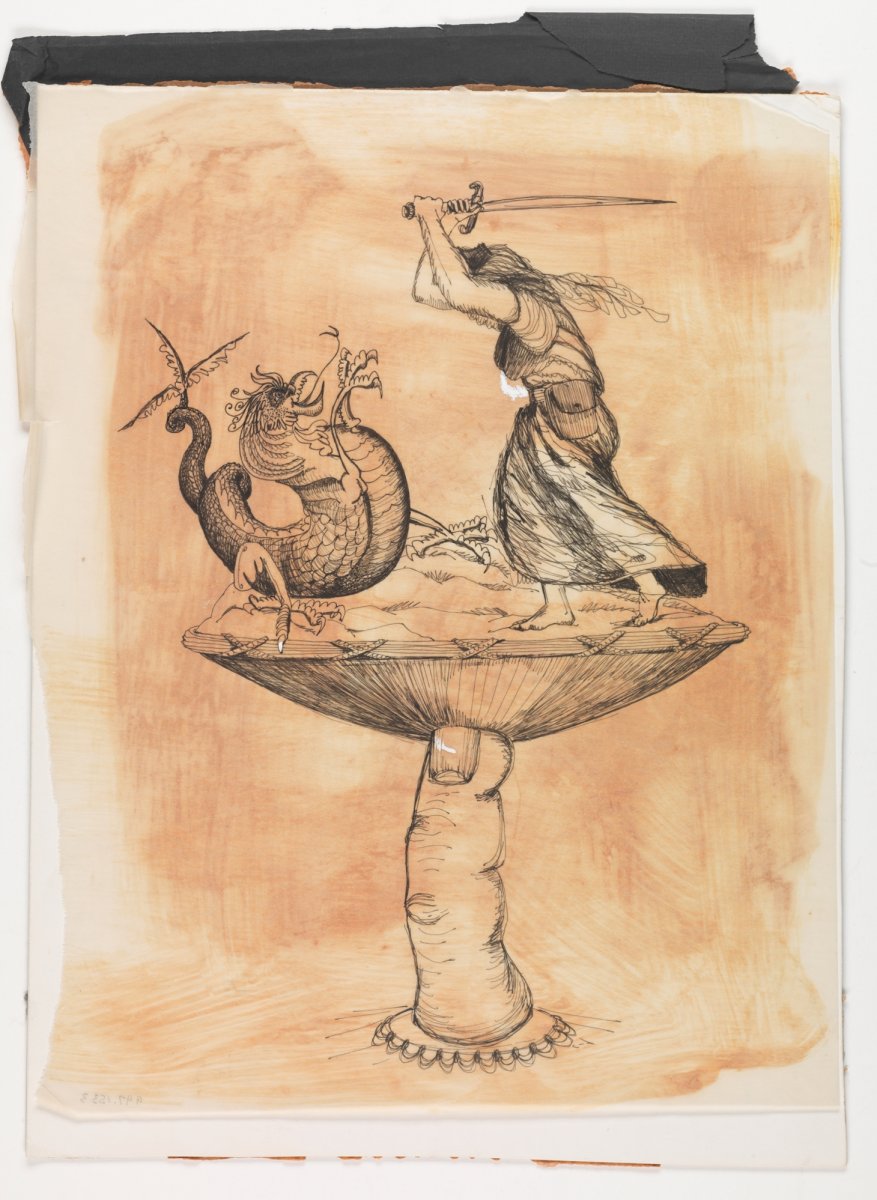

According to a newspaper report, Dali’s agent explained that “Dali envisioned the Confederate heroine ‘as a kind of modern St. George and the dragon.’ “’The facial likeness would be as near as possible to Captain Sally, but the form of the actual body would depend on whether she were in a uniform or not,’ he continued. ‘Probably the dragon would be an enlarged microbe of some kind, not the standard dragon of medieval times.’ Subsequent communications with Dali suggested that “the pedestal would be a 20-foot-high model of Dali’s little finger.”

The deliciously ironic prospect of a famous Confederate memorial boulevard in a famously conservative city becoming home to such an avant-garde public artwork understandably dominates the telling of the story of When Dali Met Sally. The denouement is of course, that Richmond was not ready for such a statue. In fact, the proposal died more or less at birth, and it has received more attention in the half-century since 1966 than it did then.

To understand the significance of the episode for the history of Monument Avenue, we must turn our attention from Dali to Sally, for the subject was central to the story and the artist peripheral.

In January 1966, Roland Reynolds, the 29-year-old son of the prominent Richmond family that made Reynolds Wrap and other household products, told the Richmond Planning Commission that Reynolds would provide aluminum for a statue to Confederate women and “Capt. Sallie [sic] Tompkins.” He assembled an ad hoc committee consisting of two prominent Virginia politicians, novelist and Civil War historian Clifford Dowdey, the widows of editor and historian Douglas Southall Freeman and novelist James Branch Cabell, several prominent club women, the Confederate Museum House Regent India Thomas, and a personal representative of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s president general.

The diminutive Sally Tompkins loomed large in Richmond Civil War history owing to the captain’s commission in the Confederate States Army that she received in September 1861. Despite the latter-day fixation with her identity as “Captain Sally,” her wartime reputation was as “Miss Sally” or “Miss Tompkins” and as a devout and conscientious keeper of a small private military hospital, not as the only woman (allegedly) commissioned as an officer in the Confederate Army.

Roland Reynolds told the press in March 1966 that Salvador Dali (with whom his family had previous contacts) “has expressed interest in the project.” A Planning Commission member opined that “if Dali were willing to work within the context of what exists on Monument ave., then Dali would probably be the best person in the world to come here right now.” When Dali’s palpably incompatible design went over like an aluminum balloon, Reynolds reminded members and the press that “we haven’t decided who will do the statue yet.”

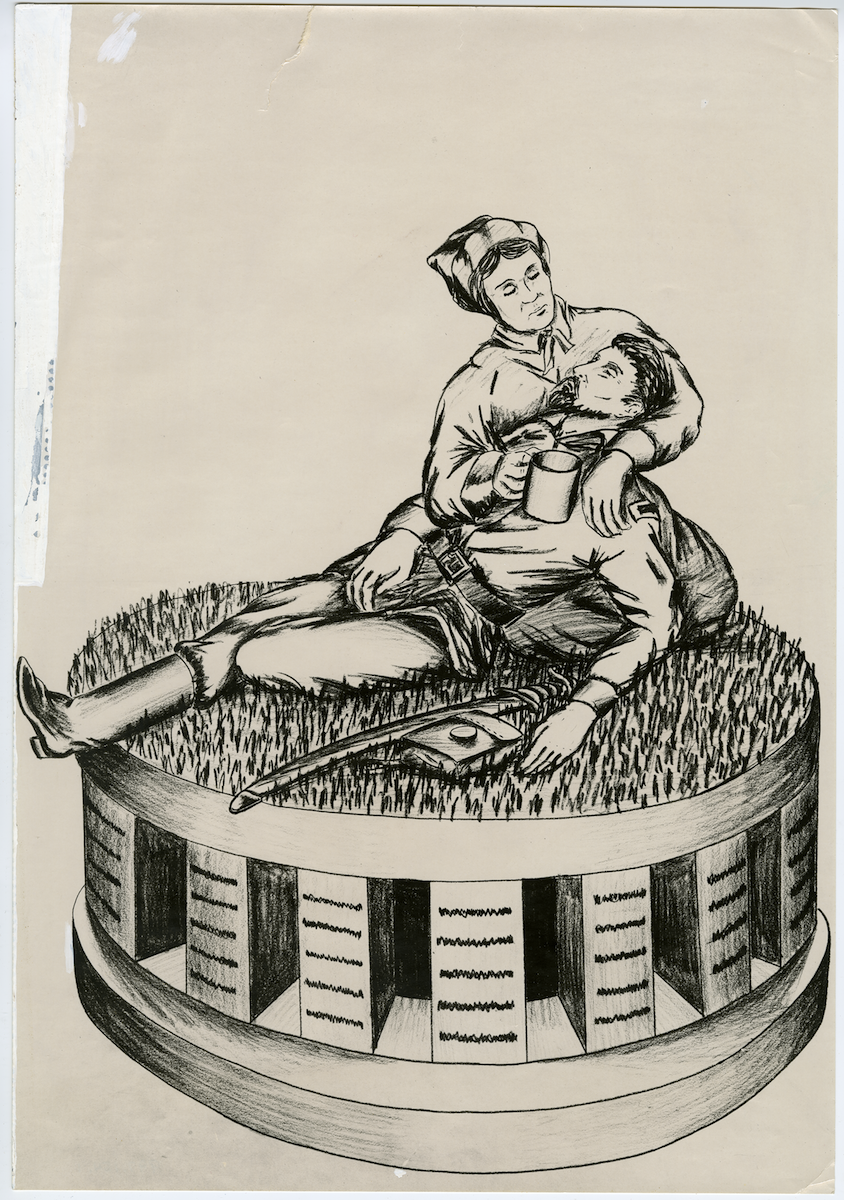

In fact, Reynolds displayed not only the oft-reprinted artist’s rendering of Dali’s concept, but the same artist’s sketches of two other designs submitted by the committee. “One drawing shows Capt. Tompkins offering water to a wounded soldier,” wrote a Richmond News Leader reporter. “The two figures are on a base of 13 vertical columns, each described with the name of a Confederate state and the names of the women who served in the Confederate army.” The second sketch “shows Capt. Tompkins holding a dying soldier. The proposed base would be draped with 13 pleats inscribed in a similar manner.”

Images Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture

After viewing those sketches and hearing a presentation from the City Planning Commission chairman about possible locations along Monument Avenue, the ad hoc committee decided to seek non-profit status, begin raising funds, and initiate a formal design competition. The committee sponsored an August 1966 “’Commemoration of Capt. Sally Tompkins and Women of the South’ parade” and a battle reenactment as a project fundraiser.

The initiative collapsed two months later when Roland Reynolds walked into a small airplane’s propeller and died of his injuries.

The aborted proposal to erect a statue to Sally Tompkins on Monument Avenue did not emerge out of thin air. Thanks to the involvement of Salvador Dali, it was the most celebrated of several proposals for new additions to Monument Avenue. Those proposals were in response to a November 1965 Richmond Planning Commission report on the future of Monument Avenue.

That report will be the subject of a subsequent post.

Recommended Reading:

Edwin Slipek, “When Dali Met Sally: The shocking and surreal Monument Avenue monument that got away,” Style Weekly, May 28, 2014. https://www.styleweekly.com/richmond/when-dali-met-sally/Content?oid=2079679