What does Memorial Day mean to you? Is it just cookouts? Solemn appreciation for the nation’s dead? Do you think it has different meanings to different people?

The ACWM Historian, John Coski, recently said that for a generation after the Civil War, Americans used Memorial Day as “showcases for still extant divisions.”

No better example of this can be found on Memorial Day in Richmond, Virginia in 1894.

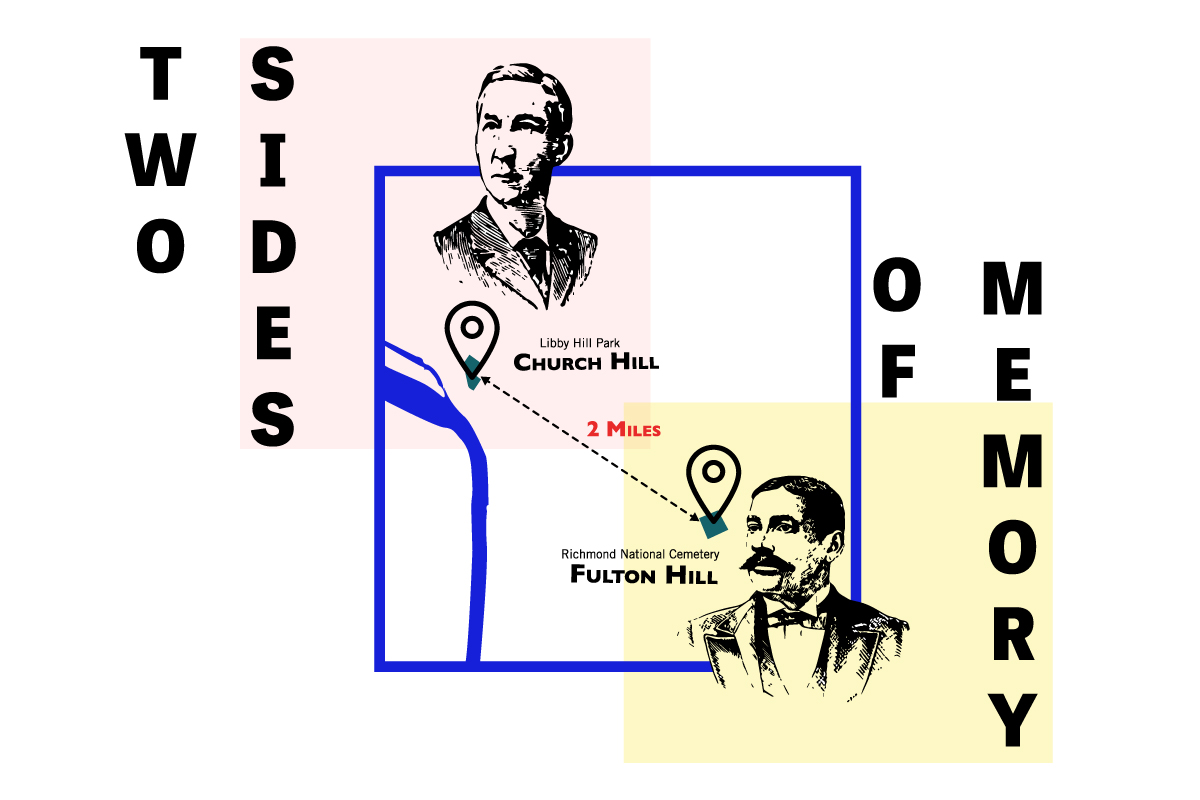

On that overcast and rainy day, two processions set out from the capital’s downtown. The first started from Jackson Ward, the heart of black Richmond. In a modest line, Richmond’s black militia, the First Battalion Virginia Volunteers joined with the white George A. Custer Post of the Grand Army of the Republic and other United States army veterans, a band, and scores of spectators. The column snaked its way four miles to the United States’ Richmond National Cemetery on Williamsburg Road.

Two hours later a raucous cavalcade of Confederate veterans, militia regiments, dignitaries and politicians, and children marching in the shape of a Confederate flag set out for Libby Hill in Richmond’s Church Hill neighborhood. They gathered to unveil the new Confederate Soldiers & Sailors Monument that towered over Church Hill and Shockoe Bottom below. (It was not, however, intended to be a Memorial Day observance. Richmond’s white women had, in the more ordinary fashion, trekked to Hollywood Cemetery to lay flowers to mark the occasion. But the Monument organizers did choose Memorial Day for the event.)

The two columns must have used the same part of Broad Street at some point before heading in two different directions.

The two keynote speakers used the same history to draw different lessons for their own day.

On Libby Hill, the Reverend Robert Cave unleashed an uncompromising defense of the Confederate States (indeed, it was so strident that it immediately sparked controversy among observers). He claimed the war had not been to defend slavery, but then described the ways that anti-slavery agitation made northerners impossible to live with.

Cave rallied his listeners. The Confederacy had been subdued, but that did not mean it was wrong. He claimed that the south had been harmonious and that gracious southerners in peace and war had always placed virtue over selfishness—unlike Puritanical northerners, in his estimation. Cave diagnosed the post-war peace as riven with selfish and corrupt values that he attributed to United States victory. The United States in 1894 he regarded as facing a “choice between anarchy and imperialism”—both bad in his opinion—and called on southerners to look to the past and rely on their steadfast virtues to resist further decline.

At Richmond National Cemetery, the speaker, Reverend Wesley F. Graham also perceived dangers. Graham, a minister at Richmond’s African American 5th Street Baptist Church chronicled the rising tide of disfranchisement, Jim Crow laws, and lynching that swept 1890s America. He recalled the bravery and sacrifices of nearly 200,000 black men who defended the United States against secessionists. “We should demand all of our rights and win by our own manhood,” he claimed, as he called upon his audience to resist the segregationist agenda.

Cave and Graham both memorialized the Civil War dead, and both used that memory to call their listeners to action; but Cave and Graham severely disagreed about what their memory called them to do.

On this Memorial Day we are being called in different directions as we confront new challenges. Conflicting recollections and differences of opinion will linger and continue to shape how we understand the holiday. How will you remember Memorial Day in 2020 in the years to come?