By Brian Palmer and Erin Hollaway Palmer

Welcome guest bloggers, Brian Palmer and Erin Hollaway Palmer. The Palmers moved to Virginia in 2013 from Brooklyn to produce “Make the Ground Talk,” a documentary that traces their journey to reveal the story of a vanished black community near Williamsburg. It was this project that led them to East End Cemetery, an African American burial ground that has suffered from decades of neglect. Brian and Erin are founding members of the Friends of East End, the all-volunteer organization working to restore the cemetery and document its history. “Freedom Fighters at Rest” was also the title of a recent History Happy Hour lecture the Palmers gave, which you can watch here.

Our interest in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) is rooted in Brian’s family history — history we knew next to nothing about until 2012, when we first visited a small cemetery on what is now Camp Peary, outside Williamsburg. Until 1942, when the U.S. government swept in and took 10,000 acres to build a Navy base, the land had been home to a constellation of communities called Magruder. Most of the roughly 200 families who settled there in the 1800s were African American; among them were Mat and Julia (Fox) Palmer, Brian’s great-grandparents.

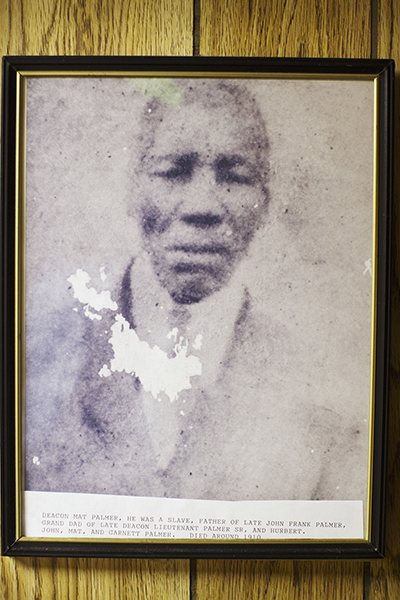

Both Mat (photo, left) and Julia had been born into slavery, he in Amelia County, she in Gloucester. During the Civil War, Julia’s family made their way across the York River to one of the government farms on the Peninsula. Mat, who was probably about 15 at the time, somehow freed himself and joined the U.S. Army after the liberation of Richmond in April 1865. A private in the 115th USCT, he never saw combat, but he likely saw more of the world during those ten months of service than he could have imagined as an enslaved child on a Goochland plantation. He mustered out in Indianola, Texas, in February 1866 and returned to Richmond for a time before heading to York County, where he married Julia in 1873 and died in 1927, passing down land to each of their 12 children — the same land the government claimed 15 years later.

Both Mat (photo, left) and Julia had been born into slavery, he in Amelia County, she in Gloucester. During the Civil War, Julia’s family made their way across the York River to one of the government farms on the Peninsula. Mat, who was probably about 15 at the time, somehow freed himself and joined the U.S. Army after the liberation of Richmond in April 1865. A private in the 115th USCT, he never saw combat, but he likely saw more of the world during those ten months of service than he could have imagined as an enslaved child on a Goochland plantation. He mustered out in Indianola, Texas, in February 1866 and returned to Richmond for a time before heading to York County, where he married Julia in 1873 and died in 1927, passing down land to each of their 12 children — the same land the government claimed 15 years later.

As far as we know, neither Mat nor Julia ever learned to read or write. We have yet to discover a hidden cache of letters or journals in a relative’s attic, much as we’ve fantasized about such a find. For Mat, we have one grainy, ghostly image — a copy of a copy — and his Union pension application, which an archivist had warned us might be disappointingly thin. And it was, though it did contain a few precious bits of information that we have found nowhere else, including the name of Mat’s owner in Goochland County.

It was our search for Mat and Julia that led us to East End and Evergreen, two of Richmond’s historic African American cemeteries. At the end of 2014, volunteers at East End had been beating back the epic overgrowth for a year and a half; Evergreen was mostly dormant. We rolled up to shoot video for a documentary project, never imagining that we’d still be working on it three years later. We also never imagined that much of those three years would be spent at East End, wrenching ivy from the ground and from trees, excavating sunken headstones, rinsing decades’ worth of dirt from hundreds, thousands, of grave markers. We had gone to film people reclaiming African American history with their hands; we ended up joining their ranks.

There is evidence that, like Mat Palmer, all four of the Civil War veterans we know to be buried at East End and Evergreen — William I. Johnson, Coleman C. Smith, Henry Wheaton, and Henry Williams — were born enslaved in Virginia. Johnson (1840–1938) describes his early life not in a Union pension file (we’re still looking for that) but in a WPA Slave Narrative. He and Mat lived parallel lives for a time, which is how we found our way to him in the first place. It wasn’t until we’d been working at East End for more than a year that we thought to ask ourselves where he might be buried. Amazingly enough, we’d been walking past his headstone all that time. We had ignored it because it was clear of vines and therefore not in need of immediate attention.

Johnson was born in Albemarle County and later given, along with his parents, to his owner’s daughter when the former died. He ended up in Goochland, a few miles from Mat; he too freed himself, walking out of a Confederate camp near Fredericksburg, with enough tobacco on hand to bribe the pickets. Until shortly before his escape, he said, “I didn’t know what the war was all about nor why they were fighting, but when the ‘Rebels’ were out on the battlefield a few pickets were left to guard the prisoners and the servants got a chance to talk to the Yankee prisoners. They explained to us about slavery and freedom. They told us if we got a chance to steal away from camp and got over on the Yankee’s side we would be free. They said if we (the Yankees) win all your [sic] colored folks will be free, but if the ‘Rebels’ win you will always be slaves. Those words got into our heads — we got together five of us, and decided to take the chance one night, and we made it.”

He and his fellow fugitives traveled on foot to Washington, where they enlisted in the U.S. Army. After the war, Johnson settled in Richmond and became a successful building contractor, sharing his life story with the WPA interviewer in 1937, a year before he died at 98. He is buried with his wife of 50-plus years, Hannah Hardaway Johnson (1858–1933), and one of their grandsons near a large magnolia tree in East End’s central section.

Large swaths of both East End and Evergreen still lie beneath a ferocious tangle of ivy, brush, and brambles. Burial records for Evergreen, though incomplete, may guide us to more veterans, when combined with information gleaned from other sources. It was just last week that we finally uncovered Coleman Smith’s plot at Evergreen after months of searching, with critical help from cemetery documents now at the Library of Virginia. No records have been found for East End. That’s frustrating, but not dispiriting. It has taken more than four years to clear about five of the cemetery’s 16 acres, roughly 12 of which probably have interments. Volunteers have unearthed nearly 3,000 headstones at East End. Progress has been slow, but steady — and striking. More discoveries await.

Brian Palmer is an independent visual journalist. Before going freelance in 2002, he served in a number of staff positions—photographer, assistant editor, Beijing bureau chief (“US News & World Report”); writer (“Fortune”); correspondent (CNN). In 2009, he completed “Full Disclosure,” a documentary about his three embeds in Iraq with U.S. Marines. Brian has taught at Columbia University, the School of Visual Arts, and the University of Richmond, among others, and is now an adjunct at VCU. Erin Hollaway Palmer is an independent editor, writer, and educator. In New York, she was managing editor of “Parade” and “National Geographic Adventure” magazines. Currently, she edits for a number of publications and nonprofits, volunteers as an adult literacy and ESL tutor, and serves as communications manager for Oakwood Arts, a new community arts center in the East End.